On Symmetry

Apparently symmetry really helps in physics problems. I was too close-minded to realize this lol. Sometimes it stares at you like ( ͡°( ͡° ͜ʖ( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)ʖ ͡°) ͡°), and sometimes its more discreet like ┬┴┬┴┤(・_├┬┴┬┴. Sometimes, its more dependent on your own training materials. For example, consider this problem:

(I used MathJax to make the $ \LaTeX $)

Problem Statement

A point charge of $q$ is placed a distance $ \frac{1}{2} a $ above the geometrical center of a square of charge of uniform surface charge density $\sigma $ and side length $ a $. Find the force on the point charge by the square.

My Original Solution

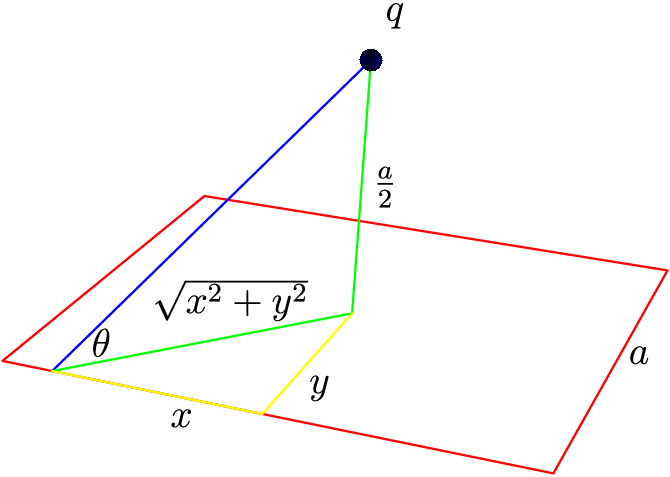

I encountered this problem after a bunch of problems that just used integration as their primary method of solution. That’s my one and only excuse for not seeing the symmetry trick immediately. We begin by assigning coordinates across the square. Let the center of the square lie at the origin and let the square lie in the $ xy $ -plane. Consider an area element $dA = dx \, dy$ located at $(x,y,0)$.

(Produced using Asymptote)

The total charge on this element, since the surface charge density is uniform, is $ \sigma \, dx \, dy$. The distance from this element to the point charge is $ \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2 }$. By Couloumb’s Law, the force on the point charge due to this area element is

\[dF = \frac{\sigma q}{4 \pi \epsilon_0} \frac{dx \, dy}{x^2 + y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2}\]However, we can’t just integrate this, but have to account for directions. We can see that the forces proportional to $ \hat{x}$ and $ \hat{y}$ both vanish, leaving only the force in the $\hat{z}$ direction.

To find $dF_z$, we multiply $dF$ by $\sin{\theta}$. From the diagram, we know that

\[\sin{\theta} = \frac{a}{2 \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2}}\]Therefore,

\[dF_z = dF \, \sin{\theta} = \left ( \frac{\sigma q}{4 \pi \epsilon_0} \frac{dx \, dy}{x^2 + y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2} \right) \left (\frac{a}{2 \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2}} \right) = \frac{\sigma q a}{8 \pi \epsilon_0} \frac{dx \, dy}{\left ( x^2 + y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right )^2 \right)^{\frac{3}{2}} }\]We now have to evaluate this integral, which may or may not be nasty. I personally like doing these kinds of integrals because I like trigonometry, but I know for a fact that this is an acquired taste, so feel free to skip to the next section if you don’t want to see the mess this will become.

\[F_z = \frac{\sigma q a}{8 \pi \epsilon_0} \int \limits_{-a/2}^{a/2} \int \limits_{-a/2}^{a/2} \frac{dx \, dy}{\left ( x^2 + y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right )^2 \right)^{\frac{3}{2}} }\]Instead of being normal people and plugging this into Mathematica or Wolfram Alpha, we are going to evaluate this monstrosity the old-fashioned way, by using trig substitutions (mainly because I’m bored and have no homework lol). We’ll evaluate the x-part first. Define $r^2 = y^2 + \left (\frac{a}{2} \right)^2 $ We can write the x-part of the integral as

\[\int \frac{dx}{\left (x^2 + y^2 + \left (\frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) ^ {\frac{3}{2}} } = \int \frac{dx}{\left (x^2 + r^2 \right) ^ {\frac{3}{2}} }\]Let’s use the standard substitution $x = r \tan{\phi}$. Then, $dx = r \sec^2 {\phi} \, d \phi $, so we rewrite this as

\[\int \frac{r \sec^2 {\phi}}{r^3 \sec^3 {\phi}} d \phi = \frac{1}{r^2} \int \cos{\phi} \, d \phi = \frac{1}{r^2} \sin{\phi} + C\]But $\sin{\phi} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + \cot^2 {\phi}}} = \frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2 + r^2}} = \frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + \left (\frac{a}{2} \right)^2 }}$, so

\[\int \limits_{- \frac{a}{2}}^{\frac{a}{2}} \frac{dx}{\left (x^2 + y^2 + \left (\frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) ^ {\frac{3}{2}} } = \frac{x}{\left (y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + \left (\frac{a}{2} \right)^2}} \bigg \vert_{-a/2}^{a/2}\]Evaulating, we find

\[\int \limits_{- \frac{a}{2}}^{\frac{a}{2}} \frac{dx}{\left (x^2 + y^2 + \left (\frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) ^ {\frac{3}{2}} } = \frac{a}{\left (y^2 + \left (\frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) \sqrt{y^2 + \frac{a^2}{2} } }\]Putting the result for this integral back into the original equation for the force,

\[F_z = \frac{\sigma q a^2}{8 \pi \epsilon_0} \int \limits_{-a/2}^{a/2} \frac{dy}{\left ( y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) \sqrt{y^2 + 2 \left (\frac{a}{2} \right)^2 }}\]We make the substitution $y = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} a \tan{\phi}$. This implies that $y^2 = \frac{1}{2} a^2 \tan^2 \phi$ and $dy = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} a \sec^2 \phi \, d \phi$.

\[\int \frac{dy}{\left ( y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) \sqrt{y^2 + \frac{a^2}{2} }} = \frac{4}{a^2} \int \frac{\sec{\phi}}{2 \tan^2 \phi + 1}\]Normally, I’d give up and resort to Wolfram Alpha here, but notice what happens when you multiply the integrand by $\cos^2 \phi$. The result is

\[\frac{4}{a^2} \int \frac{\cos \phi}{1 + \sin^2 \phi} d \phi\]The rest of the integral is actually quite easy. Let $u = \sin \phi$, so $du = \cos \phi \, d \phi$. Then,

\[\frac{4}{a^2} \int \frac{du}{1 + u^2} = \frac{4}{a^2} \tan^{-1} {u} = \frac{4}{a^2} \tan^{-1} {(\sin{\phi})}\]Recall that $\sin \phi = \frac{\tan \phi}{\sqrt{1 + \tan^2 \phi}} = y \sqrt{\frac{2}{a^2 + 2y^2}}$. Finally,

\[\int \frac{dy}{\left ( y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) \sqrt{y^2 + \frac{a^2}{2} }} = \frac{4}{a^2} \tan^{-1} \left (y \sqrt{\frac{2}{a^2 + 2y^2}} \right)\]Taking the limits, we see that

\[\int \limits_{- \frac{a}{2}}^{\frac{a}{2}} \frac{dy}{\left ( y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) \sqrt{y^2 + \frac{a^2}{2} }} = \frac{4}{a^2} \left ( \tan^{-1} \left ( {\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}} \right) - \tan^{-1} \left ( {- \frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}} \right ) \right ) = \frac{4 \pi }{3 a^2}\]Finally, we can see that the force is

\[F_z = \frac{\sigma q a^2}{8 \pi \epsilon_0} \int \limits_{-a/2}^{a/2} \frac{dy}{\left ( y^2 + \left ( \frac{a}{2} \right)^2 \right) \sqrt{y^2 + 2 \left (\frac{a}{2} \right)^2 }} = \frac{\sigma q}{6 \epsilon_0}\]The Solution I Found 2 Minutes Later :’)

The force on the point charge by the square is equal to the force on the square by the point charge by Newton’s Third Law, so we can compute

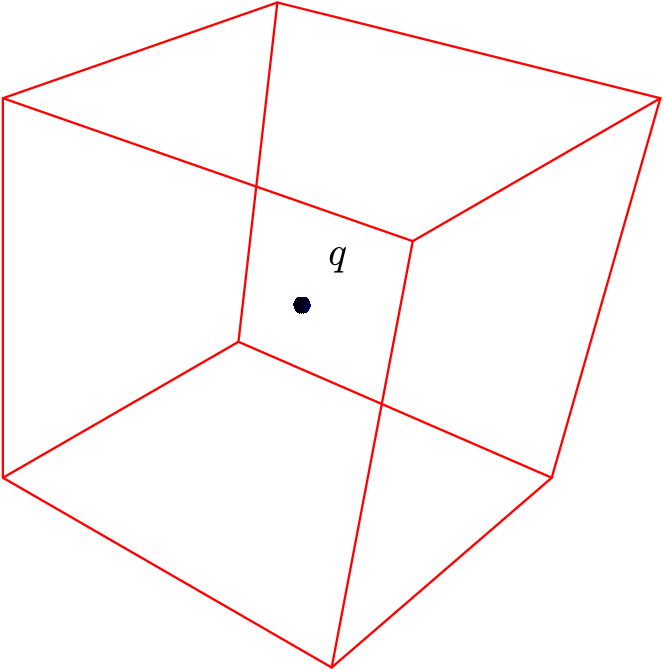

\[F = \int dF = \int E \, dQ = \sigma \int E \, dA\]The integral here is easy! It’s just the flux. Normally, we would have used a big integral like above, but we can consider the following: let the square be part of a larger cube of side length $a$, so that the charge is at the center of the cube. See the diagram below:

The flux through the whole cube must be $\frac{q}{\epsilon_0}$. The flux through each side must be the same by symmetry and this is the crucial step, as we couldn’t solve the problem without doing the integrals above.

Since there are 6 sides in a cube (duh), the flux through a side is $\frac{q}{6 \epsilon_0}$, we can conclude that

\[F = \frac{\sigma q}{6 \epsilon_0}\]