My First Experience With Plasma Physics

These are my notes for Chapter 1 of Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion by Francis F. Chen.

MLA Citation - Chen, Francis F. Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion. 3rd ed., Springer International Publishing Switzerland, 2016, Springer Link, link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-22309-4.pdf

1.1 Occurence of Plasmas in Nature

The Nature of the Universe

According to NASA’s WMAP, the universe is composed primarily of dark energy (71.4 %). Following that is dark matter (24 %). Both last and least is regular matter (4.6 %).

About Plasma

Plasma is an ionized gas. This means that at least one of the electrons in an atom that constitutes the plasma has been stripped free.

Plasma is also called the “fourth state of matter. When solids are heated, they turn into liquid. When liquids are heated, they turn into a gas. When gases are heated enough to ionize them, a plasma is created.

A plasma is made up of both ions and electrons, so there are a rather large number of electric fields everywhere inside the plasma. Moreover, these charged particles are always moving, so there are also magnetic fields being created. The particles can now interact with each other through their magnetic and electric fields, significantly increasing their range of possible motions. Moreover, external magnetic fields are often applied to a plasma in order to control it.

Usually, plasma only exists in a vacuum (e.g. outer space) In order to create it in a laboratory, we need to pump air out of a vacuum chamber to be used to create the plasma in. Earth is obviously not a vacuum, so plasmas don’t occur naturally. It is rare to see plasma outside of lightning bolts, arouras, fluorescent tubes, and plasma TVs.

Saha Equation

This can be seen through the Saha ionization equation, developed by Indian astrophysicist Meghnad Saha in 1920. The equation predicts the amount of ionization in a gas at thermal equilibrium. Let $n_i$ be the numerical density of the ionized atoms and let $n_n$ be the numerical density of the neutral atoms. Let $T$ be the temperature of the gas (we use Kelvin here). Let $k$ be the Boltzmann constant. Let $U_i$ be the ionization energy of the gas - i.e. the amount of thermal energy needed to be given to an atom to remove its outermost electron. The Saha equation mathematically states the relationship as

\[\frac{n_i}{n_n} \approx \left (2.4 \times 10^{21} \right) \frac{T^{\frac{3}{2}}}{n_i} e^{- \frac{U_i}{kT}}\]Recalling that nitrogen makes up the highest amount in the Earth’s atmosphere, we can approximate the atmosphere as made entirely of nitrogen, which has an ionization energy of $14.5$ eV. For air at room temperature, $n_n$ is approximately $3 \times 10^{25} \, \text{m}^{-3}$. Room temperature is around $300$ Kelvin, so by the Saha equation, we can estimate that the fractional ionization in the air we breath is extremely low:

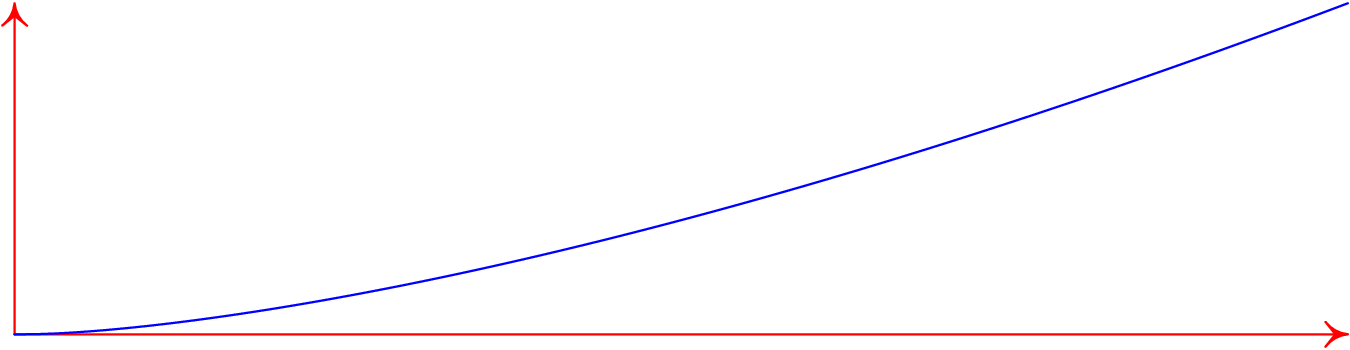

\[\frac{n_i}{n_n} \sim 10^{-122}\]We graph the visual representation using Asymptote:

As you can see, as temperature is raised, the amount of ionization increases rapidly, eventually making $n_i = n_n$. That’s why plasmas can’t occur naturally on Earth, as life couldn’t easily coexist with the plasma.

Physical Interpretation

We don’t want to overuse the Saha equation, as it is a very rough approximation. However, we do want to emphasize the physical principles behind it. From statistical mechanics, the atoms in a gas have a spread of thermal energies. Intuitively, an atom with more energy will have a higher chance of knocking out an electron when colliding with another atom. Moreover, the atoms will obviously collide with more force.

1.2 Definition of Plasma

Not all ionized gases can be called plasmas, as there is always some degree of ionization in a gas, no matter what temperature. Therefore, its nice to have a definition to rely on:

A plasma is a quasineutral gas of charged and neutral particles which exhibits collective behavior. (Chen 1.2)

We now discuss collective behavior. In a plasma, there are charged particles: positive ions and negative electrons. These charges produce electric fields and their movement produces magnetic fields.

Now, we consider the effect of two differently charged regions of plasma (separated by a distance $r$) on each other. Each exerts a force proportional to $1/r^2$. However, the solid angle inscribed increases proportionally to $r^3$, so the force actually increases as you go further out, as long as you stay within a region that contains plasma.

In collisionless plasmas, the electromagnetic forces are much larger than the collisions between atoms, so the collision forces can be neglected completely.

By collective behavior, we mean the following: consider a portion of plasma embedded in a larger portion of plasma. From the long-range electromagnetic forces we have discussed above, the forces on the atoms in the portion depend not only on the behavior of the portion, but also the atoms within the larger portion. That is, the behavior of an atom in plasma doesn’t just depend on its local conditions, but also its global conditions.

1.3 Concept of Temperature

Its useful to review our concept of temperature. Consider a gas in thermal equilibrium, which will have particles of all velocities. The probability of having a certain velocity is proportional to the Boltzmann distribution:

\[f(v) \propto \exp(- \frac{mv^2}{2kT})\]Where $k$ is the Boltzmann constant and $T$ is the temperature of the gas. We can see that the higher the temperature, the more likely it is that velocities of the particles are higher. It can be shown from this distribution that for $f$ degrees of freedom, the average energy is

\[\langle E \rangle = \frac{f}{2} kT\]Since energy and temperature are so closely related, it is customary in plasma physics to give temperatures in units of energy. To convert, we suppose that $E=kT$ to avoid confusion on the value of $f$. Therefore, if we consider 1 eV, which is $1.6 \times 10^{-19}$ J, this corresponds to

\[T = \frac{1.6 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J}}{1.38 \times 10^{-23} \, \frac{\text{J}}{\text{K}}} = 11,600 \text{K}\]Therefore, 1eV corresponds to 11,600 K. By a 2eV plasma, we mean that $kT$ = 2 eV, or $\langle E \rangle = $ 3 eV in 3 dimensions.

Interesting Phenomena

It is possible that a plasma can have more than one temperature (and by the work above, energy) at once. Often, the ions and electrons have separate velocity distributions, with different temperatures $T_i$ and $T_e$. This usually happens because because the collision rates of the ions and electrons are different (the electrons have much less mass and are much smaller). Each species can be in its own thermal equilibrium.

Moreover, when there is a magnetic field applied can cause multiple temperatures to occur. That’s because the Lorentz force has components both parallel and perpendicular to the magnetic field, so the velocity must have components perpendicular and parallel to the magentic field. This leads to Boltzmann distributions with temperatures $T_{\perp}$ and $T_{\parallel}$.

Misconceptions

Finally, people need to know that high temperature $\neq$ a lot of heat. This is due to heat capacities and density changes. For example, the electron temperature inside a fluorescent light bulb is around 20,000 K. When you touch it, it doesn’t really feel that hot. That’s because the density of electrons inside a fluorescent bulb isn’t that high, especially not compared to a gas at atmospheric pressure. Therefore, the amount of heat transferred to the bulb’s exterior is also rather low, as the electrons don’t strike the wall that much. Many plasma laboratories deal with temperatures on the order of $10^6$ K, but their particles are at rather low densities, so the heating of the walls isn’t really a concern, as long as an appropriate material is chosen.

1.4 Debye Shielding

Now we consider Debye shielding, named after Dutch-American physicist and physical chemist (he won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1936 for his work on dipole moments and x-ray diffraction) Peter Joseph William Debye. Consider what happens when we try to put an electric field in a plasma, by inserting two conducting balls connected to a battery. Since the electrons and ions in the plasma are mobile, they assemble around these balls in a cloud. Specifically, the electrons go to the cathode and the ions go to the anode. This effectively cancels out the field as sufficiently large distances from the balls. If there was no thermal motion, then there would be just as many charges in the cloud as in the ball, and no electric field would be present in the plasma outside of the clouds. On the other hand, if there is thermal motion, then at the edge of the cloud, the ions and electrons will be able to be free. Therefore, potentials on the order of $\frac{kT}{e}$ will leak into the plasma and cause an electric field to exist there.

Next, we try to compute the approximate thickness of this cloud of charge. Imagine that the potential on the surface of the ball is held at $\phi_0$ by the battery and is unaffected by the thermal motion of the particles. We want to compute $\phi(r)$. Assume that $\frac{m_i}{m_e} = \infty$, so the ions don’t move. Using the Boltzmann distribution for a potential energy $q \phi$, we see that the distribution is proportional to

\[f(v) \propto \exp{(- \frac{mv^2}{kT} - \frac{q \phi}{kT})}\]Integrating over $v$, we find that the density of electrons $n_e$ is, recalling this distribution is also a Boltzmann distribution, with maximum density $n_{\infty}$

\[n_e = n_{\infty} \exp{-\frac{e \phi}{kT}}\]This means that Poisson’s equation is, in the region where the thermal energy is much higher than the electrostatic

\[\frac{\partial^2 \phi}{\partial r^2} = \frac{e n_{\infty}}{\epsilon_0} \left (e^{\frac{e \phi}{kT}} - 1 \right) \approx \frac{n_{\infty} e^2}{\epsilon_0 kT } \phi\]Solving after defining the Debye length as $\lambda_D = \sqrt{\frac{\epsilon_0 kT}{e^2 n_{\infty}}}$, we find that

\[\phi(r) = \phi_0 \exp{- \frac{r}{\lambda_D}}\]The Debye length is the measure of shielding distance that we were looking for. As density increases, so does $\lambda_D$, as we expect. Furthermore, it decreases with temperature, as more thermal energy means greater ability to break free of the potential applied by the battery. Finally, it is electrons only that are able to do the shielding, as they are much more mobile (we have assumed that the ions don’t move at all).

Quasineutrality

If the dimensions $L$ of the system are much larger than the Debye length $\lambda_D$ of the plasma, then whatever local charge concentrations arise, they can be shielded using the Debye effect, leaving most of the remaining plasma free from electric fields. One condition for an ionized gas to be a plasma to be classified as a plasma is $\lambda_D \ll L$.

1.5 The Plasma Parameter

Consider a sphere that has a radius of the Debye length. The number of particles $N_D$ in this sphere is

\(N_D = \frac{4}{3} \pi n \lambda_D^3\) This is an estimate for the number of particles that is in one of the Debye clouds. In order for the cloud-forming behavior to be valid, we must have enough particles, so

\[N_D \gg 1\]1.6 Criteria for Plasmas

Third Condition

The third condition for being a plasma has to do with collisions. In order to be weird like a plasma, we need an ionized gas to not collide frequently, or else it behaves like a normal fluid, and electromagnetic interactions are insignificant compared to collisions. If $\omega$ is the frquency of typical plasma oscillations and $\tau$ is the mean free time between oscillations, then we require

\[\omega \tau > 1\]Putting it All Together

The three conditions arise

\[\lambda_D \ll 1\] \[\omega \tau > 1\] \[\omega \tau > 1\]